Re-post with correction

Re-post with correction

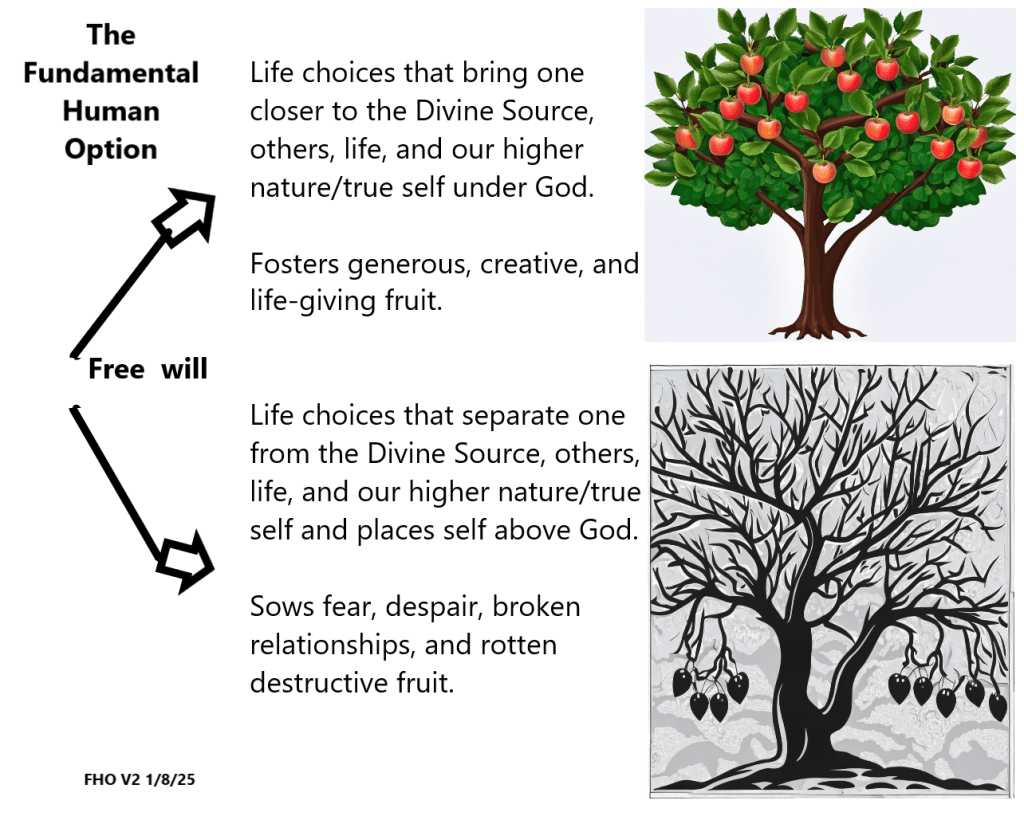

As we continue our journey deeper into spiritual activism, we pick up the sixth essay of this series with where we left off—replacing vices with virtues and the process of reorienting one’s being to the good, the true, and the beautiful. As I currently understand it, the good, true, and the beautiful are the common philosophical categories representing the highest expression of being within the three dimensions of the human psyche or soul—the will, the mind, and the emotions and thus in turn, in and through life lived, individually and collectively.

Individual ideals or virtues can be ordered within one of these three primary categories. Thus, as we work to reorient our being and lives in the direction of our ideals, choice by choice, day by day, it is essential to maintain honest awareness of where we are in the present (Note: Most of us need a spiritual director, friend, and/or community to help us as we can easily deceive ourselves here). All the progress made in the initial phases of our healing and maturing work provides a solid foundation of self-awareness which continues to reveal our character flaws, strengths, emotional wounds and vulnerabilities, gifts, and habitual patterns more clearly and allows us to compassionately examine how they influence and shape our lives and our happiness (Friendly reminder: This is a not a linear process but a life-long, iterative, ripening of being).

Our growing self-awareness sheds light on which of “the three beasts” (i.e., the symbols used in Dante’s DC to represent the gates of the cardinal vices highlighted in Essay 5) is the most predominant inner obstacle to our reorientation of beingness. As we start to “connect the dots” of our inner world, we can select spiritual practices most suited for facilitating ongoing deep change (i.e., reorientation).

For example, in the spiritual literature, fasting is often encouraged as an essential core practice for “lust of the flesh” (sexual lust, gluttony, and sloth); tithing and charitable giving to include money, possessions, and volunteer service for “lust of the eyes” (greed and worldly sorrow), and prayer and meditation or contemplation for “lust of life” (wrath, envy, and spiritual pride).

It is important to reemphasize that across the world religions prayer and meditation or contemplation are essential core practices for all of us seeking to heal, mature, and transform in service to a higher common good (see chart below). There are many excellent resources, spiritual and religious, available to help inform and guide one’s selection of spiritual practices to include Richard Foster’s classic Christian guidebook, “Celebration of Discipline” and those cited in my book, Ten Developmental Themes of Mindful Leaders, Table 5.1.

| Wisdom Tradition | Examples of Transformative Practices Associated with Wisdom Traditions of the West | ||||

| Christianity-Inner | Lectio Divina (sacred reading) | Centering Prayer (meditation) | Contemplation | Prayer | Service |

| Islam-Sufism | Chanting | Prayer | Breathing Exercises | Music & Dancing/Whirling | Meditation |

| Judaism-Kabbalah | Study of the Torah, Talmud, the Zohar and other sacred texts | Meditation | Prayer | Pilgrimages to Holy Places | Shabbat/Sabbath |

Table Source: Frizzell, Denise (2018). Ten Developmental Themes of Mindful Leaders.

As stated previously, initially, and potentially for a significant period, reorienting to the good, the true, and the beautiful may feel like an inner battle. However, each time we reject a habituated destructive choice (a vice) for a desired good (a virtue or ideal), we are strengthened in our efforts by a budding inner aliveness, sense of freedom, and happiness, as well as improving interpersonal relationships, and growing life satisfaction. Over time, we experience a growing ease or disposition for the good, true, and beautiful coupled by a simultaneous increasing distaste for our old harmful habits.

Furthermore, as we reorient more into our new, higher selves, we may notice an increasing sense of unity with other people, nature, and overall LIFE as well as an expanding love for self (not as in the selfishness of our old, false self but as in a growing dignity and self-respect), for other people, nature, and God/Spirit/Divine Source, which readies us for entering into the transforming phase of our journey to spiritual activism –receiving and responding to the movements of inspiration for the well-being of others and the common good.

To be continued.

As we pick up the next leg of our journey to spiritual activism, let us review where we are now. We have our meditation or centering prayer-contemplation practice (ideally, a consistent daily practice of at least 15 minutes/day at a regular time which one slowly, gently builds upon to at least 30 minutes a day not to exceed an hour a day unless one is working with a reputable, advanced spiritual teacher).

We selected and have begun studying our initial map of the territory –a trustworthy, comprehensive psycho-spiritual conceptual framework (see essays 1-3 of this series for some options). We have a spiritual friend and/or a support group with whom we can authentically discuss our efforts and experiences. We also may be journaling and working with a therapist, coach, or spiritual director.

As part of our ongoing healing phase of our journey, we are also practicing self-observation with the intention of “recognizing” when afflictive or negative emotions arise within us, and we are starting to cultivate the capacity to “refrain” from associated hurtful and destructive habituated reactions and patterns.

As we continue these practices (remember this is a life-long spirally journey!), we may notice that we are becoming less reactive, more self-aware, and more able to self-regulate. Thus, we can start to move further into the maturation phase of our three-phase model of the journey to spiritual activism–healing, maturation, and transformation coupled by the increasing arising of and responsiveness to heart-felt inspiration for action that decreases suffering and increases justice, harmony, ecological sustainability, etc. in the world.

Now we are ready to add releasing and replacing to our practice of recognizing and refraining. First, we can release some of the charge of an afflictive emotion or memory with the help of simple techniques such as “pausing” and taking a few deep breaths, or gently putting attention on one’s feet while feeling contact with the floor below. These can be coupled with a silent inner statement of an internal observation, such as “anger arising” which allows for recognition/acceptance of an emotion and restraint while constructively discharging potentially charged energy coupled with an emotion.

According to psychology and neuroscience, it only takes 90 seconds for charged emotional reactions to work their way through our bodies. Thus, if/when a trigger emotion lasts longer than that, we are feeding it with our thoughts and perpetuating the effects on self and others. While recorded over 15 years ago, Dr. Jill Taylor’s TedTalk (and related book, A Stroke of Insight) is as inspiring and relevant now as it was then on this topic.

With some of the energy surge of an afflictive emotion released, we can now replace a negative reactionary habit with a preferred mode of being or ideal. This next phase moves us into the domain of values and ethics which for many people is associated with their faith tradition or spiritual path. Thus, I encourage you to select the values and ethical ideals that most inspire and move your heart to a higher good (e.g., compassion, sustainability, stewardship, justice, etc.) and away from automatic self-centered, negative, hurtful, and destructive modes of being. This replacing phase marks a conscious choice to more mature, responsible, and compassionate speech and actions, and can include a supportive silent prayer, mantra, or saying in the moment such as “love is my decision,” “I have more than enough,” “time is my friend,” the Buddhist Loving Kindness mantra (or metta), or some other anchor word, scripture, mantra or the 12-Step slogans (e.g., “Keep it Simple”).

There are many options for support here to include scripture and literature from one’s chosen or inherited religious tradition or spiritual path. I have benefited from the study of many teachers across the world’s wisdom traditions. Thus, while I have been shaped and inspired by my study and practice of world religions and philosophy, I most resonant with the values taught and lived by Christ Jesus in the Christian Gospels, the Unitarian Universalist Seven Principles, and the Eightfold Path of Buddhism.

In addition, virtue ethics, with roots in Greek philosophy and Christian writings on virtues and vices is and has been highly informative, instructive, and inspirational to me. Most recently, this material includes Brant Pitre’s writings on the topic in his book, Introduction to the Spiritual Life, and Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung’s book, Glittering Vices.

To be continued

For this second essay on the topic of spiritual activism, I would first like to refine my working definition of the concept to the following:

Intentionally reforming (i.e., challenging to the status quo/business as usual) words and actions for the common good, informed and inspired by a growing understanding (and possibly direct experience) of the ultimate unity of all life coupled with an intensifying love for others, life, and the Source (i.e., God, Ground of Being, Universal Love, Divine Light etc.) AND, over time, a deep healing/ liberation/recovery from destructive habitual patterns, in part, by regular, consistent, long-term spiritual practices.

After posting the first essay on this topic, I realized that my initial definition did not explicitly capture the deep healing component of the spiritual journey that I intended. This latest definition attempts to do so with, “AND, over time…”

While different terms are used in the inner traditions of our world religions as well as paths of personal transformation not directly associated with a specific religion (e.g., The Fourth Way), spiritual healing or awakening from spiritual sleep requires the choice to turn inward to begin self-observation with an open, compassionate, honest orientation to increase self-awareness or self-knowledge.

The beginning of awakening from spiritual sleep is to first acknowledge that one is asleep, and that there is a painful degree of discontent present or perhaps, an element of unmanageability to our life (many of us avoid this work until reaching this point). We admit to ourselves and the God of our understanding, “no, I truly do not, got this.” Through regular self-observation, we begin to notice our habitual patterns and character defects (Twelve Steps), negativities (the Fourth Way), or shadow (Carl Jung). As difficult as it is to explain, we begin the spiritual healing or liberation process as soon as we start to see these aspects of ourselves, because they reveal a distinct observing self from the destructive act or mode of being.

As stated in essay one of this series, the material that I share in these essays on spiritual activism is not original. It comes from the systems of personal transformation, those associated directly with religions and some that are not, that I have studied over 20+ years. However, I may not always be able to remember which tradition or what teacher I may have received a teaching from, but I will strive to make those connections for readers. Of note, the world’s religious traditions all have inner spiritual traditions (i.e., paths to spiritual healing, maturation, transformation, and union) as well as more visible and known outer expressions or exoteric traditions with which we are more familiar.

While some spiritual paths such as the Twelve Steps integrate prayer and meditation later in the healing process, my study of and experiences with Buddhism, Contemplative Christianity, and other systems of self-transformation (e.g., the Fourth Way) inform my encouragement to consider a meditation practice, coupled with other self-observation practices, at the beginning (and throughout) of the spiritual journey process unless one has experienced severe trauma and has not yet engaged in any type of therapy or has only recently begun therapy. I am not suggesting an either/or here as I have benefited from both in my journey (i.e., traditional counseling and spiritual healing teachings and practices), but sharing my understanding of sequencing especially if/when one experienced significant trauma and has not yet engaged in any traditional counseling work.

Meditation or simply moments of silence and solitude are essential for the spiritual journey, because they support the cultivation of mental space in which greater clarity and objectivity can arise. Starting and maintaining a regular (at least five times a week if not daily) meditation or silence practice, will provide the essential foundation for the journey to spiritual activism as we begin to slow down enough to become to see ourselves and to start gaining self-awareness. Initially, this growing self-awareness can be extremely difficult. For example, when I started meditating over 15 years ago, I was shocked by the busyness of my mind, the speediness of being, and the anger underlying my activism and much of my life. This was not pleasant, but it was liberating, because I was able to start seeing and facing my habitual patterns and self-destructive and hurtful ways, which provided the needed opening for deep change work to begin.

Such internal seeing and recognizing opens the door to deep change by shedding light on the option to interrupt the automatic or habitual reaction by refraining and replacing, both simple to say but not easy to do as we all know from personal efforts to break unhealthful habits.

To be continued.

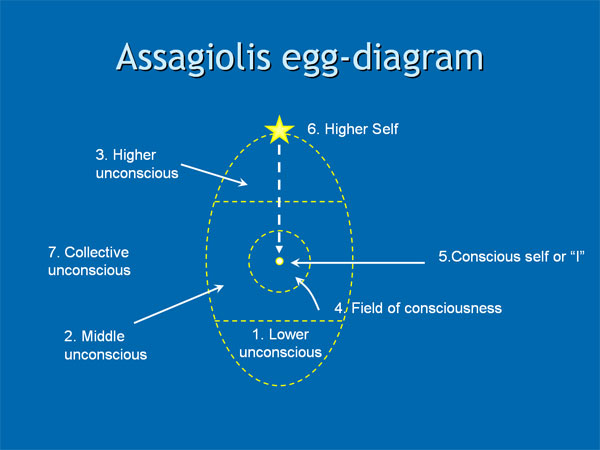

Psychosynthesis is a holistic approach to psychology, developed by Roberto Assagioli (1888-1974) that incorporates psychoanalysis, but significant transcends it by emphasizing health, development, and spirituality. Assagioli illustrated his view of the human psyche in his “egg-diagram” (see Figure) with seven elements:

Figure. Assagioli’s Egg Diagram

Source: Kenneth Sorensen, https://kennethsorensen.dk/en/. Used with permission.

1. The Lower Unconscious

The lower unconscious, according to Assagioli, contains the basic psychological activities that conduct the operative and intelligent coordination of the body and bodily functions. This dimension of the psyche also holds one’s foundational drives and animalistic urges, as well as emotionally intense established thematic patterns (i.e., psychological complexes), dark dreams and fantasies, and some pathological disturbances such as paranoid delusions, uncontrollable urges, obsessions, and phobias.

2. The Middle Unconscious

The middle unconscious, according to Assagioli, includes psychological dimensions comparable to waking consciousness with ready access to it. Life experiences are integrated, and standard cognitive and creative intelligence activated in a type of psychological incubation before entering the field of conscious awareness.

3. The Higher Unconscious or Superconscious

The higher unconscious or superconscious is the region that holds our highest inspirations, aspirations, and intuitions for ourselves, humanity, and our world. This realm is also the source of our higher emotions such unconditional love and higher intelligences. It also holds the deeper experiences of insight, contemplation, and bliss, as well as potentials for higher spiritual experiences and psychic abilities.

4. The Field of Consciousness

For Assagioli, the field of consciousness, a term he thought useful but not quite precise, referred to the part of our personality of which we are conscious, including the thoughts, bodily sensations, emotions, desires, and impulses we are able to see and evaluate.

5. The Conscious Self or “I”

The conscious self or “I” is the term Assagioli used to refer to the “the point of pure-awareness,” not to be confused with the field of consciousness highlighted above, which refers to the content of experience. The conscious self or “I” refers to the experiencer. He compared the “I” to a projector light and field of consciousness to a screen onto which images are projected.

6. The Higher Self

Unlike Freud’s psychoanalysis, which only includes a lower unconscious, Assagioli’s psychosynthesis includes the Higher Self or soul depicted above the conscious self in the egg diagram. According to Assagioli, one can experience the Higher Self through the use of psycho-spiritual practices such as meditation.

7. The Collective Unconscious

Assagioli’s collective unconscious, similar to Jung’s conceptualization of the term, refers to universal, nonpersonal common forms or archetypes that surround and influence us on a collective level. Assagioli distinguished between primitive, archaic forms and higher, progressive forces of a more spiritual nature.

Although not depicted in Assagioli’s original egg diagram (though some contemporary illustrations do include it), another key element of psychosynthesis is the concept of subpersonalities. Subpersonalities, similar to Jung’s persona, refers to parts or formed habit patterns in the human psyche, conscious and unconscious, that we repeatedly express in our lives. For the healthy person, subpersonalities are conscious and in the field of self-awareness and self-regulation. In psychosynthesis, subpersonalities may reside in the lower, middle, or higher unconscious, unlike Jung’s persona or false self. Additional fundamental concepts of psychosynthesis, which highlight stages of Self-realization, include self-knowledge, self-control, disidentification, unifying center, and psychosynthesis, as the peak stage in his model.

Disidentification refers to the necessity of separating oneself (the conscious I) from overidentification with everything outside or beyond oneself. Overidentification can happen any time we identify with an aspect of our life experiences such as a subpersonality, our ethnicity, fear, anxiety, or a role to such an extent that it dominates our lives. Thus, healing and growth opportunities lie in seeing when and where one overidentifies and, with the help of exercises and practices, severing the control of the overidentification on oneself or “I.”

Over time, former objects of overidentification can be healthily integrated into the middle unconscious and accessed more intentionally. The unifying center refers to the discovery or creation of an ideal around which one can reach or reorganize one’s life. Psychosynthesis, in addition to referring to Assagioli’s entire approach to psychotherapy, refers to the peak of the developmental process that establishes a new personality around a primary unifying center: one that is “coherent, organized and unified” (2000, p. 23).

Consequently, personal will (the Will) is a highly significant concept in psychosynthesis such that Assagioli dedicated a book on the topic entitled, The Act of Will. The will is an element of Assagioli’s Star Diagram of Six Psychological Functions (see Figure 5-2/Not included in this essay), which he developed later in his life to complement the egg diagram of the psyche. Lamenting the state of psychology in 1958, Assagioli is quoted as stating, “After losing its soul, psychology lost its will, and only then its mind and senses” (2007, Foreword).

Furthermore, Assagioli held the view of the existence of a transpersonal will, which he viewed as a dormant potentiality for most people. Assagioli’s transpersonal will aligns with what Maslow referred to as “higher needs” and the growing field of transpersonal psychology refers to using a variety of terms that include Christ consciousness, unitive consciousness, peak experiences, mystical experiences, spirit, oneness, and other such similar concepts.

As mentioned above, psychosynthesis proposes a dynamic five-stage healing and realization process (see Table—Not included in this essay). Stage zero highlights the predominate stage of humanity, characterized by what Assagioli called, the “fundamental infirmity of man.” John Firman (?–2008) referred to this human condition as “primal wounding”; wounding resulting from not being seen and heard for who we truly are by significant others in our lives. Stage 1 relates to the tuning in of one’s inner experience and the cultivation of greater self-awareness. Self-awareness is the foundation of all growth and development. Without self-awareness, we tend to react out of instinct and habitual responses or what Firman referred to as, the survival personality. As self-awareness expands, we start to see our tendencies, preferences, and shortcomings.

Eventually, we (often with the help of supportive practices or a skilled guide) begin to free ourselves or disidentify from our habitual thoughts, feelings, reactions, and roles, thereby cultivating the witness or individual observer “I” (Stage 2). Over time, we may start sensing a more expansive identity or connectedness to life and begin to feel new vocational urges, creative impulses, or directive promptings (Stage 3). From a psychosynthesis perspective, this involves surrendering and inviting a more intimate, conscious relationship with the Highest Self or soul. The fourth stage of psychosynthesis corresponds to a period in which we are formally responding to the invitations of the Highest Self (in contrast to the personal self or ego in its contemporary usage) and developing more spiritually.

Survival of wounding, exploration of the personality, the emergence of I, contact with the Highest Self, and response to the Highest Self represent the five stages of psychosynthesis. However, Assagioli and others (e.g., Firman & Gila, 2002 and Brown, 2009) cautioned that these stages do not represent a set developmental sequence, but potential responses to the human condition that can occur at any age.

It is important to note that Assagioli presented psychosynthesis in two subcategories: personal psychosynthesis and transpersonal psychosynthesis. The emphases of personal psychosynthesis are self-awareness and self-regulation. The foci of transpersonal psychosynthesis are on the realization of one’s Highest Self/soul and the actual psychosynthesis, the reformation of the personality around a new unifying center or ideal.

Numerous practices and exercises align with psychosynthesis overall and in these two categories. Thus, to identify a narrow set of core practices is inconsistent with this reality. However, it is fair to say that visualization, drawing, self-observation, and meditation are common practices among psychosynthesis-oriented counselors, therapists, and coaches. In addition, as highlighted above, disidentification is a core concept of psychosynthesis and activities aimed at freeing oneself from overidentifying with a dimension of our being or life other than the center of pure awareness or “I.”

Given today’s pressing global challenges and the subsequent demands on human beings, psychosynthesis offers a holistic and hope-filled paradigm for the journey toward healing, well-being, self-actualization, and Self-realization.

Note: Modified excerpt from my book, “Ten Developmental Themes of Mindful Leaders”

How can we relax and have a genuine, passionate relationship with the fundamental uncertainty, the groundlessness of being human?

Pema Chödrön

In 1989, business scholar, Peter B. Vahil coined the phrase, “permanent white water” to describe the changing business environment. Vahil may have been foreseeing life in the 21st century in as the management and leadership literature recently adopted the military acronym, VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) to describe the global environment. Furthermore, management guru Gary Hamel frequently reminds his audiences that the “nature of change is changing.”

Consequently, a growing body of leadership literature emphasizes the importance for leaders to enhance their tolerance for uncertainty or ambiguity. For example, leadership scholars Ron Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky’s propose that adaptive leadership is critical given the reality of VUCA. Heifetz and his colleagues argue that “diagnostic failure” is at the root of humanity’s inability to solve our most pressing challenges. They argue that leaders are approaching humanity’s unprecedented global challenges as technical challenges, challenges with knowable solutions.

However, as evident in the repeated failure of technical solutions, the challenges humanity faces are adaptive challenges. Adaptive challenges are beyond current individual and collective knowledge, capacity, and expertise. Therefore, they require higher psychological maturity, as well as capacities and competencies that many, if not most, leaders have not yet developed.

This developmental gap makes leaders and the organizations they lead vulnerable to costly missteps, performance declines, and legitimacy losses. While the literature purporting the necessary competencies for effective global leadership is vast, three comprehensive categories, highly related to the capacity to tolerate uncertainty, frequently emerge: perception management, relationship management, and self-management. Furthermore, a growing body of mindfulness scholars have indicated positive correlations between these three comprehensive categories and MBIs which my research on mindful leaders supports.

And I think in the past I probably would have made a much quicker perhaps more decisive decision in the moment and not embraced that time of interim or uncertainty. So I think mindfulness allowed me to do that and to say ‘it’s okay not to have all the answers right now,’ and let it kind of be. (Male middle manager in the health care industry)

I think embracing that sense of adventure, that sense of adventure and sometimes adrenaline that I had been avoiding [with] people sometimes …because I associated it with maybe danger or risk, but now being much more comfortable living on that leaning-toward perspective as opposed to kind of leaning on the safe side of the fence. (Male middle manager in the health and wellness industry)

Thus, mindful leaders experience a growing tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity which supports them not only in their work roles but in all areas of their lives. The VULA environment appears to be here to stay for the foreseeable future, perhaps intensifying. Thus, the critical decision we each face is whether we will attempt to navigate the white waters of our lives in the boats we have or start building stronger boats.

This essay is an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Ten Developmental Themes of Mindful Leaders with an expected publication of October-November 2018.

When written in Chinese, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity. John F. Kennedy

As emphasized in the management literature, employees frequently resist organizational change for a variety of reasons to include fear of the unknown. As we all know from our own lives, resistance to change also occurs on the individual level as well as the organizational level. Consequently, individuals and collectives tend to be more open to learning and growth opportunities when they are faced with a personal or professional crisis. When a personal and professional crisis propels a leader to move into unknown territory in and through constructive action, it can serve as a transformative learning opportunity.

Transformative learning occurs when radically new experiences induce a tectonic shift in perspective in the way one views him/herself, others, and the world. Longtime leadership scholar and author, Warren Bennis refers to these types of transformative events as crucibles. He and co-author Robert Thomas wrote in their seminal article on the topic that highly effective leaders are the people who can find meaning in and learn from their most painful and difficult crucibles. Such leaders emerge from the ashes more confident, strong, and more committed to the things that deeply matter to them.

Effective leaders that use their crucibles as learning opportunities have growth mindsets. In her work on mindsets, Carol Dweck makes the distinction between fixed and growth mindsets. Leaders with fixed mindsets view themselves and others as being born with a limited amount of capacity and potential for learning. Thus, the emphasis is on protecting their image and proving themselves. From the fixed mindset, failure is feared and avoided at all costs.

In stark contrast, leaders with growth mindsets hold the view that they and others can build upon the capacities they with which they were born. They see failure as a natural and welcomed dimension of learning and development. Leaders with a growth mindset also know that success does not simply happen to them. They celebrate that success (as they define it) requires passion, effort, training, and yes, failure. The growth mindset is illustrated in the stories shared by the mindful leaders interviewed for my 2015 study (insert link).

At the time, I was really struggling with depression and anxiety, and it had been recommended for me to take that (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) class. And the unexpected side effect was the really powerful impact of helping me create a daily mindfulness practice, which for me is a combination of meditation, daily taking time out for just mindfulness moments, trying to do things in general, everything I do, more mindfully, being more aware of it. (Female middle manager and marketing researcher)

But in terms of my more recent delving into it (mindfulness), it’s been maybe about 3 years, 2 and a half to 3 years where I’ve been seriously getting into meditation, and to be perfectly honest with you, what prompted me was my wife’s illness and being able to get myself to a place of being able to deal with and handle that. The self-awareness, the centeredness, the calm, the ability to sort of control the uncontrolled, I think were the more attractive things about it and just not only that, the relieving of stress was one of the things that attracted me to it, ‘cause I was undergoing a lot of stress and I felt like I needed to get a handle on it. I exercise, I walk, I do those things, but you know, I felt that there was a, maybe a better way to attain that, I think, so yeah. (Male senior manager and administer in higher education)

Thus, leaders yearning to be and become more self-aware and effective turn their crises into opportunities for constructive action. By choosing growth mindsets over fixed mindsets, they open themselves to unforeseen possibilities that alter their lives in powerful and profound ways. So, next time you face a personal or professional crisis, follow the lead of mindful leaders who turned their crises into opportunities to turn inward and experiment with mindfulness meditation and other transformative practices.

Note: This essay is an excerpt from the forthcoming book, Ten Developmental Themes of Mindful Leaders by Denise Frizzell, Ph.D. Denise offers leadership and organizational coaching and consulting for spiritual activists, evolutionaries, progressive change agents and their organizations. Visit https://metamorphosisconsultation.com/schedule-a-coaching-appointment/ to schedule a FREE 20-30 minutes exploratory session.

We need the compassion and the courage to change the conditions that support our suffering. Those conditions are things like ignorance, bitterness, negligence, clinging, and holding on. Sharon Salzberg

We need the compassion and the courage to change the conditions that support our suffering. Those conditions are things like ignorance, bitterness, negligence, clinging, and holding on. Sharon Salzberg

Jane Dutton and Monica Worline’s book on compassion in the workplace, Awakening Compassion at Work, offers a helpful lens in which to think about the significance of our seventh developmental theme of mindful leaders, self-other empathy and compassion. They equate empathy with compassion, the feeling of “suffering with” another person in a way that emotionally connects and elicits a compassionate response. It is important to note that self-compassion is an essential element of empathy and compassion toward others as it is extremely difficult to give to others that which you do not give to yourself.

Dutton and Worline’s research indicates that employees who experience empathy and compassion from managers-leaders and the organizational context via culture, climate, structure, etc. feel seen and affirmed in their pain and thus bounce back more quickly with increasing satisfaction and organizational commitment. Furthermore, employees have more constructive emotions in the workplace while exhibiting more supportive behavior toward other stakeholders. Therefore, the growing empathy and compassion of mindful leaders act as a positive contagion in the workplace on the employee and organizational levels as illustrated in the following narratives.

Another thing is just a kind of emotional empathy. Like I think I’m much better able to read emotional states. I’m still working on that, but a lot of times I can very quickly pick up on, ‘Oh, this person is distraught right now. I can’t really come down on them about some technical question. I need to, like, address their personal issues.’ And, so that empathy is, again, something that builds very naturally. (Male middle manager and professor)

I’ve used mindful self-compassion prior to some very difficult conversations that I’ve had to have with team members. Sometimes performance improvement kinds of conversations. And looking at how can I as a leader be as empathetic as possible when I’m delivering, say, a complaint that’s been shared by a patient or a family member or even an employee to an employee kind of thing. (Male middle manager in the healthcare industry)

It is different now. I mean now, it is part of my life and I have gained so much wisdom along the way and I have noticed so much about myself which helps me see in that in other people. I can see when other people are stuck in the stress cycle and I am not taking it personally. I am able to bring some compassion to them and some kindness and help calm them even though they don’t know I am doing that. So we come to a space where we can problem solve together. (Female entrepreneur and former healthcare senior executive)

Some of us may not view empathy and compassion as significant qualities of organizational managers-leaders or for our workplaces. However, the mindful leaders in my 2015 study, as well as a growing body of research to include the work of Wolin and Dutton, indicate differently. These two lines of scholarship (mindful and compassionate leadership) demonstrate that being able to “stand in another’s shoes” and see as they see and feel as they feel, enhances the subjective states of both the manager-leader and the direct report as it relates to how they feel toward one another and toward their organization. Furthermore, as highlighted above, such positive inner states ripple outward and favorably impact the larger culture, climate, and performance levels.

Note: This essay is an excerpt from the forthcoming book, Ten Developmental Themes of Mindful Leaders by Denise Frizzell, Ph.D. Denise offers leader/leadership and organizational coaching and consulting for progressive change agents and organizations. Visit https://metamorphosisconsultation.com/schedule-a-coaching-appointment/ to schedule a FREE 20-30 minutes exploratory session.